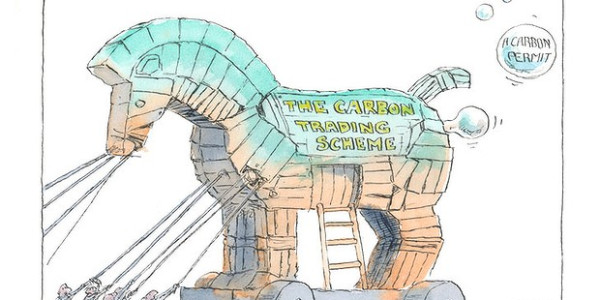

April 18, 2013 Illustration: Malcolm Maiden. The collapse of Europe’s latest attempt to breathe life into its moribund carbon trading scheme is a hammer-blow for proponents of a global carbon trading system. So much has gone wrong with Europe’s scheme that a global trading regime may be out of reach for decades, even if the carbon price recovers. Europe launched its trading system in 2005, and it quickly became the world’s carbon trading hub, for European permits, but also for ones generated in other markets, including the world’s largest issuer of permits, China. European regulators issued too many permits when they launched the scheme, however. The glut was hidden for a couple of years as Europe and the world surfed to the top of the boom that led to the global financial crisis, but once the crisis hit, it emerged as a potentially fatal design flaw. Europe’s carbon price was above €20 a tonne in 2008, before the sovereign debt phase of the global crisis emerged and Europe plunged into a deep recession. By February this year it was at €5 a tonne as recession conditions kept industrial activity, power generation, emissions and demand for permits down. Then on Tuesday in Brussels, the European Parliament narrowly voted against a plan to shore up prices by quarantining surplus carbon credits, and the carbon price fell to €2.6 or $3.34 a tonne. The plan to ”backload” excess credits by withdrawing them, holding them for about five years and then reinjecting them into a European economy that regulators hoped would by then be growing strongly enough to push demand for permits higher will probably be resubmitted, but there is no great hope that the vote will be different. The collapse in European carbon trading prices directly pressures the carbon reduction regime that the Labor government has launched because the intention is to switch from a carbon tax to a carbon trading scheme in 2015-16, and link the Australian scheme to the European system at that time. Existing and proposed prices for Australia’s scheme are far above those that now exist in Europe. The carbon tax was introduced last year at a price of $23 a tonne, and the government’s budget papers predict a price of $29 a tonne by the time the scheme shifts to carbon trading. If the European price stays down, Australia’s price will be below $10 a tonne after trading begins. Permits will be cheaper than expected, government revenue from the sale of permits will be lower, budget balances will be pressured and the government’s commitment to carbon scheme compensation packages that range from power generators to households will be reviewed. The broader message from the collapse of carbon trading in Europe is, however, that a carbon trading scheme cannot be relied on alone to set a pathway that leads to sustained emissions reduction. In a regime where carbon trading was an ineffective forcing mechanism in this country, for example, the separate target for at least 20 per cent of Australia’s energy to be sourced from large-scale renewable energy sources by 2020 would become a much more important part of the emission reduction equation. Carbon trading is designed in part to be a pathway for the flow of emission credits to where they are needed. Credits are underpinned by a carbon price, and if that carbon price rises they have positive value – are ”in the money” in options market parlance. Emissions reduction in a functioning carbon trading system is therefore not just driven by steps emitters take to reduce their emissions as carbon costs rise, but by ”green” investment rate of return sums that are sweetened by the profitable sale into the trading system of credits earned by renewable energy projects. The collapse of the European price has been so severe, however, that the investment incentive component of the trading scheme has been seriously undermined. Funds in China and elsewhere that were set up to create green projects assumed a much higher carbon price than now applies, and the profitable sale of carbon credits that enabled their projects to hit their rate of return hurdles. They are now stranded, and their investors have retreated. Underlying rate of return sums on green projects could be similarly affected when trading begins if the carbon price is lower than expected, but Australia’s separate target for at least 20 per cent of Australia’s energy to be sourced from renewable energy sources is a partial backstop. Energy prices would be lower without it, but it is a key renewable energy investment forcing mechanism: while it exists, energy companies must either buy or build renewable energy generating capacity. Given that and given the state of the political polls, the Coalition’s attitude to the 20 per cent target is going to be crucial, and so far it is not clear. It has pledged to kill the carbon tax and axe Labor’s $10 billion Clean Energy Finance scheme, but Opposition Leader Tony Abbott was circumspect about the renewable energy target when pressed earlier this month, saying only that a Coalition government would subject it to a ”serious review”. Read more: http://www.theage.co…l#ixzz2QpHmrUr5

Carbon Trading Scheme Facing Strife

This entry was posted in Investment, investments, News, Property, Taylor Scott International, TSI, Uk and tagged australian, carbon, chat, china, green, illustration, investment, investments, property, scheme. Bookmark the permalink.