Taylor Scott International examines the many ways in which the housing market in London differs from the rest of the UK, and even from the rest of south east England. London is a global city, with governance arrangements that are different to the rest of the country, including a mayor with responsibility for housing, planning and infrastructure. These arrangements make London more akin to an autonomous city-state, quite dissimilar to the rest of the UK.

Taylor Scott International examines the many ways in which the housing market in London differs from the rest of the UK, and even from the rest of south east England. London is a global city, with governance arrangements that are different to the rest of the country, including a mayor with responsibility for housing, planning and infrastructure. These arrangements make London more akin to an autonomous city-state, quite dissimilar to the rest of the UK.

The population of London differs from the rest of England in having a higher proportion of young adults and fewer elderly people. This produces a quicker natural rate of increase in population, creating additional pressure on the housing stock.

Population growth, migration and tenure

London is the fastest growing region in the UK. The 2011 census recorded its population at 8.2 million, an increase of 12% in a decade. The figure is expected to reach nine million by 2018. London currently has around 3.3 million households, a total that is expected to grow to just under four million by 2031.

The city also has a high rate of inward migration, both from overseas and within the UK. For many of those moving into London, the private rented sector is well suited. But migrants from overseas include a relatively high proportion of people at the ends of the income spectrum, fuelling prime house prices in central London and adding to the need for social housing.

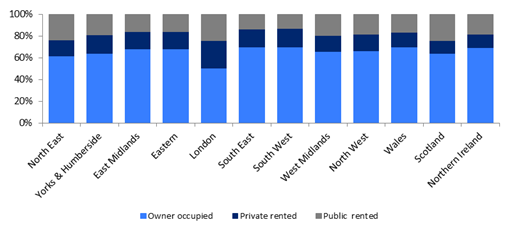

London’s tenure profile differs from the rest of the UK. Among all regions, it has the lowest rate of home-ownership (at 50%) and the greatest reliance on the private rented sector (26%). The city also has 24% of its population living in social housing, a high proportion matched elsewhere in the UK only in north east England and Scotland.

The proportion of London’s population in the private rented sector has grown in the last decade, while home-ownership and social renting have both declined. The home-ownership rate peaked in the capital as long ago as 2000, and so its relative decline precedes the credit crunch. Since then, owner-occupation has dropped more steeply than elsewhere in the UK, declining by 10 percentage points. And the rate of decline has quickened more recently.

London’s housing stock has grown by a little over 200,000 properties in the last decade, but we estimate that the number of homes in owner-occupation has declined by 179,000. Over the same period, the social housing stock has declined by 18,000 properties, while the number of private rented homes has grown by 427,000.

Chart One: Tenure profiles of UK regions, % of total stock, 2010

The London property market

Despite having a smaller percentage of its population in owner-occupation than any other UK region, London accounts for a high proportion of house purchase loans. With property prices in London higher than anywhere else in the UK, the proportion of lending by value advanced to borrowers in the capital is even greater.

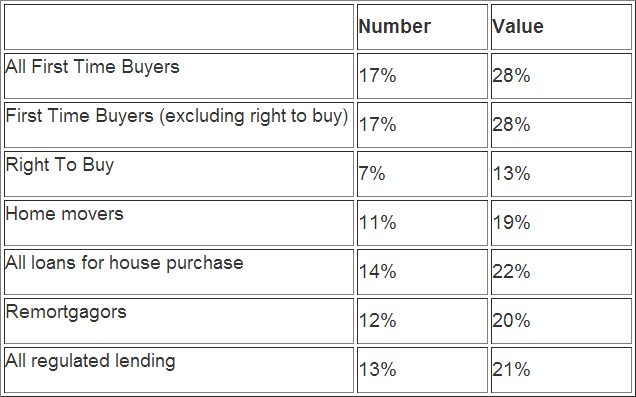

Table One: London’s share of regulated mortgage lending, %, year ended September 2012

The decline in the number of homes in owner-occupation has contributed to a reduction in the number of property transactions in London, although this has been partially offset by a brisker pace of turnover since the credit crunch. For many years, London has managed to sustain activity levels, despite the significant affordability problems caused by high property prices.

Loans for house purchase in London increased in the third quarter, as in the rest of the UK. A total of 20,600 house purchase loans, worth just over £5 billion, were advanced in the capital – an increase of 22% on the previous quarter and 4% on the same period last year. This rate of growth was higher than in the rest of the UK, where house purchase lending increased by 13% on the second quarter. The number of loans for house purchase in the third quarter was also the highest since the last three months of 2007.

Property prices

House prices in London have bucked the national trend. In most parts of the UK, prices peaked in the second half of 2007 and then declined by around one-fifth, before stabilising in 2009 against a policy of aggressive monetary easing. However, prices in London have shown the strongest recovery and, according to Nationwide Building Society, the capital is the only region in which property values have now regained pre-credit crunch levels, a point reached in spring this year.

In June 2012, the average mix-adjusted house price in the capital was £392,000, compared with an England average of £240,000, according to the Office for National Statistics. Part of the resilience of London property prices is explained by the city’s global status. The political stability of the UK, combined with a 20% depreciation in the value of sterling since the credit crunch, has made the capital an attractive destination for international investors in central London property.

Another important characteristic of the capital’s housing market is the significant variation in property prices within London. This presents flexibility for those wishing to buy but who find themselves priced out of expensive areas. There are often options to buy in other districts, which contributes to the process of gentrification of areas of the capital.

First-time buyers

One of the peculiarities of the London property market is that first-time buyers are responsible for a higher proportion of purchases than in the rest of the UK, despite higher property prices. Although overall levels of owner-occupation in London are lower than in the rest of the UK, Table One shows that 28% of all lending to first-time buyers nationally last year was advanced to purchasers in the capital.

From our regulated mortgage survey, we know that first-time buyers in London are a little older than elsewhere in the UK. The average difference in age is less than two years, but that is enough to affect the ability to save towards a deposit. However, we also estimate that more than 70% of first-time buyers in London get help from their parents or other relatives. The proportion of unassisted first-time buyers in the capital is estimated at 28%, compared to 34% in the UK overall.

The average first-time buyer household in London has an income of £50,000, compared to £34,000 elsewhere in the UK. Larger incomes in the capital, the older average age of first-time buyers (and a longer period in which to build up savings) and high levels of assistance mean that those purchasing their first home in London put down a larger proportion of the price of the property as a deposit than elsewhere in the UK – despite significantly higher average prices. First-time buyers in London purchase properties with an average loan-to-value ratio of 75% – a figure that has not changed since 2008 and is lower than the rest of the UK (80%).

There may be other factors explaining the capacity and appetite to buy among Londoners, including first-time buyers. People have perhaps been conditioned over time by persistently higher property prices. Londoners may simply have got used to spending a larger share of their income on housing, and be more willing than in other parts of the UK to stretch themselves to get on the housing ladder.

The dynamics of the London market – and the capacity of first-time buyers to transact in the capital, despite the challenging circumstances – helped ensure that 10,000 purchasers took out a mortgage to buy their first home in the capital in the third quarter. That was the highest quarterly total of first-time buyers in London for almost three years.

Housing policy

Quite simply, London needs more homes. There were just over 20,000 new homes built in the capital in 2011-12, 17% of England’s total. Four years ago, the Greater London Authority, currently working on an as yet unpublished housing strategy, estimated that the capital needed 32,600 new homes every year just to keep up with demand.

Affordability is a key problem in all tenures, with demand driving up prices as supply falters. The cost of renting, as well as buying, is significantly higher in London than in the rest of England. Housing association rents are almost 27% higher than the English average, while private rents are more than 70% higher.

The lure of London for overseas investors creates particular problems for would-be owner-occupiers, while the capital needs a funding model for affordable housing that is sustainable and certain. The current arrangements are due to expire in a little over two years, and registered providers and those funding them need certainty about how development plans will be funded from April 2015 onwards.

In the drive to improve housing supply and affordability, the needs of mortgage lenders and commercial investors are often overlooked. There are limits to innovation at a time when mortgage funding remains constrained. Our over-riding message is that simple, standardised funding models, operating on the right scale, are the key to ensuring that innovative solutions can work in London.

Conclusion

The London housing market differs in many ways from the rest of the UK. It has different demographics, movements in population and patterns of tenure. And living in all tenures in the capital is more expensive than the national average. But there are also some fundamental similarities. London suffers from a lack of housing supply and affordability problems like much of the rest of the UK.

Another key difference is that London has a mayor, with responsibility for housing strategy and investment. The capital needs a single, comprehensive housing strategy that blends national policy with measures specifically to address London’s problems. We look forward to publication of the finalised London housing strategy. Lenders want to be recognised as part of the solution, and will work constructively with the government, the mayor and the Greater London Authority on solutions to the special housing challenges of the capital.